BBC Travel's correspondent recounts the tradition of the Bali Aga people, who allow the bodies of the deceased to decompose under the open sky in the shade of an ancient magical tree that, according to beliefs, eliminates the odor of decay.

"There lies my cousin," my guide Ketut Blen explains, pointing to the skull and pile of clothing under an unassuming canopy made of interwoven palm and bamboo branches. "But I feel nothing as I look at him."

The cemetery in the Balinese village of Trunyan, where residents send the deceased on their final voyage in canoes for their bodies to decompose under the open sky, is a secluded spot surrounded on all sides by steep slopes covered in impenetrable jungles. It is situated on the shores of a massive mountain lake of volcanic origin - just a stone's throw away by boat from the native village. On this island, where the majority of Balinese Hindus cremate the bodies of the deceased, Trunyan stands uniquely.

Fellow Balinese from the Bali Aga tribe, who typically settle in remote villages primarily in the northeast of Bali, isolated from the outside world, are among the oldest inhabitants of this island: Trunyan existed as far back as the year 911 AD. Like most Balinese, the Bali Aga adhere to a unique branch of Hinduism, but each village group - including the one centered around Trunyan - also venerates its own religious rituals and beliefs.

For instance, in Tenganan, the most well-known village populated by the Bali Aga, they spin girls for marriage in a bamboo "devil's wheel" and weave magical fabric. In Trunyan, they practice ritual lashings with rattan shoots and allow the bodies of the deceased to decompose under the open sky.

As explained to me by Blen, there are actually two cemeteries in Trunyan: the one we are currently in is intended for those whose life journey is considered complete.

"These deceased were all married," he says. "If someone dies before getting married or drowns in the lake, we bury them in the ground."

In the religion of the Trunyan people, the animation of natural phenomena plays an even larger role than in the branch of Hinduism followed by most Balinese.

The village itself, beneath which rises a large temple with 11 pagodas corresponding to the 11 "funeral towers" in the cemetery, is situated in a very perilous location. Nestled right under an active volcano on the shores of an restless crater lake, it is at the mercy of two dangerous elements - fire and water - at once.

The volcano named Batur has shaped the way of life and death here for centuries.

"We have a volcano here," explains Blen. "That's why we can't cremate people. There could be problems with the volcano."

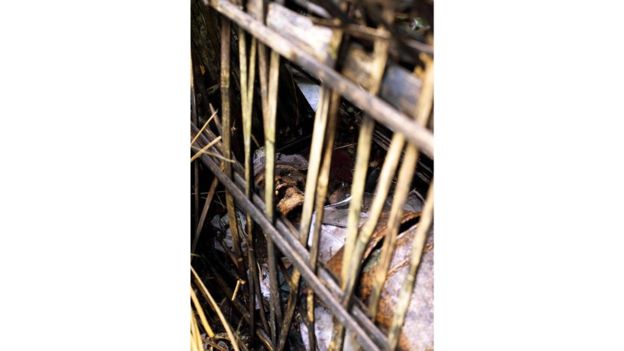

Initially, the deceased were left under the open sky out of fear of angering the volcano, which is now identified with the Hindu god Brahma. The number 11 holds great significance in Hinduism, which is why there are only 11 dome-shaped cells made of palm and bamboo branches in the cemetery. When all of them are filled, the local residents move the oldest remains to a bone depository, also located under the open sky.

However, sometimes there is nothing to move. Bones often simply disappear from the cells - perhaps monkeys are to blame, roaming the forest in hopes of finding food offered as gifts to the gods and the deceased.

Despite all the dirt and scattered trash around the cemetery, where a human thigh bone could easily lie amidst a pile of empty plates next to a worn sandal, there is a peculiar tranquility prevailing here.

Surprisingly, the scent of death is hardly noticeable.

The deceased, dressed in their favorite clothes, rest peacefully under colorful umbrellas. And the eye sockets of the skulls in the bone depository seem to radiate serenity: their earthly journey has ended, and their spirits are far away from here.

The latest addition to this cemetery was a village priest, a mangku, who passed away 26 days before my arrival. Blen's cousin has been lying here for several months.

Since bodies can only be brought to the cemetery on specific auspicious days, and families often need to gather funds for the funerals, sometimes a body remains in the house for several days or even weeks. To prevent decomposition during the extended waiting period, locals use formaldehyde.

In the village of Puser, located on a hillside and belonging to the same district as Trunyan, there is also an open-air cemetery. As we sailed past it in a boat, a repulsive stench of decaying bodies hit my nose - the foul odor was perceptible even from a hundred meters away.

However, there was no such foul smell at the Trunyan cemetery. I peered through the palm fronds of the cells into the empty eye sockets of a person, whose skull still showed patches of charred flesh, and I only sensed a faint hint of decay.

And it seems, not just thanks to formaldehyde. Over the cemetery looms a massive, moss-covered tree with tangled branches, resembling an ancient banyan tree. The locals believe that this tree, which they call "taru-menyan," or "fragrant tree," overpowers the smell of decay.

"This tree is magical," explained a friend of Blen's, Ketut Darmayas. "In a house, the bodies would smell. But here, no, and it's all because of this tree."

This lakeside fishing village is remarkable not only for its burial ritual and magical tree.

To make collective decisions, all the residents still gather at the bale agung - open-air platforms that form the center of this three-tiered village. And once a year, usually in October, young men don elaborate costumes made of banana leaves and lash each other with rattan shoots in a ritual dance called brutuk. Why? To bless the temple and protect the village and its inhabitants from harm.

Nevertheless, the most distinct feature of Trunyan remains its strangely tranquil cemetery. There, surrounded by reminders of human mortality and the inevitability of death for everyone, I asked Blen how he manages to look at the smoldering remains of his cousin without grieving.

For a while, they conversed in Balinese with Darmayas. "He's only sad at home," Darmayas said. "[In the cemetery], he doesn't feel the sorrow."

"Why?" I asked again.

"That's our culture," Darmayas simply replied.

Because in Trunyan, as everywhere, death and grief are just a part of the culture. It's just more apparent here.

You can add one right now!