Excerpt from the article "Traditional Bali in the Modern World" from the book "Southeast Asia: Current Development Issues".

The population of Bali is approximately 4 million people, of which about a third live in rural areas, although the boundaries between small towns and villages on this island are sometimes quite blurred.

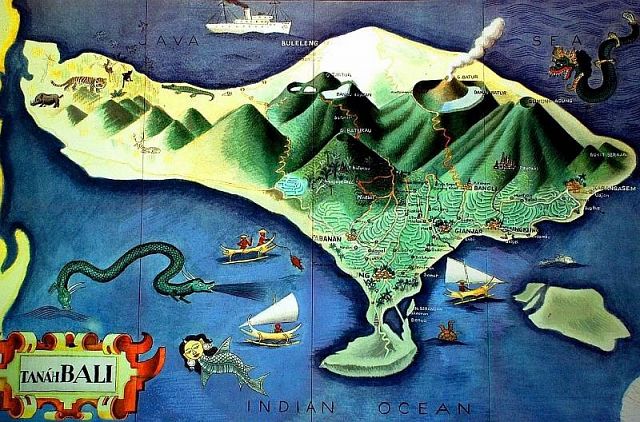

The island is divided into large districts called "kabupaten" - Badung, Gianyar, Klungkung, Karangasem, Bangli, Buleleng, Jembrana, Tabanan. The island's capital, Denpasar, is designated as a separate district and is not part of the "kabupaten".

The most densely populated "kabupaten" is Badung (with over 700,000 people), while in Klungkung, the population is around 200,000 people.

The main part of today's Balinese are descendants of people from the Javanese Majapahit Empire, which collapsed under the pressure of Islam in the early 16th century.

Balinese Aga

The indigenous inhabitants of the island are a people known as "Bali Aga," which means "mountain Balinese," although they do not like this name themselves and prefer to be called "Orang Bali Mula" ("original Balinese") or "Bali Turunan" ("Balinese descended from the heavens"). The majority of Balinese still consider Bali Aga to be rough and uncultured men. This is also reflected in their religion: while the majority of Bali's population follows Hinduism, specifically its Balinese variation, the Bali Aga predominantly practice animism and worship spirits.

Bali Aga also worship gods who, in their beliefs, govern the world, led by the supreme deity Ratu Sakit Panchering, whom they believe resides in the main temple of each of their villages.

Bali Aga villages, such as Tenganan or Asak and Bungaya, are also known for strictly adhering to rules and norms of behavior (awig-awig), which were developed in each village many centuries ago and are carefully preserved by local elders.

The village of Trunyan

The most well-known village of Bali Aga is the village of Trunyan, situated on a remote narrow strip of the coastal area of Lake Batur, surrounded by mountains on three sides.

To reach this village, one usually takes a boat from the opposite shore of Batur, although visiting the village itself can be quite problematic. The locals of Bali Aga tend to be somewhat aggressive towards guests and usually demand money for entry, and sometimes even for the opportunity to leave Trunyan freely.

The village is famous for not cremating or burying the deceased, but instead placing them in special woven cages under a sacred tree on the edge of the village. According to Balinese beliefs, the aroma emanating from this tree "neutralizes" the foul odor of the body, a sentiment confirmed by the author of these lines. The tree in Trunyan is truly unique and possibly has no analogues, especially considering its study is unlikely due to the specific nature of the local inhabitants. It takes the form of a huge sprawling tree, reminiscent of a banyan tree, but its exact appearance is unknown.

Also located in Trunyan is the main temple of Bali Aga, where the 4-meter-tall statue of Ratu Sakit Panchering is hidden from prying eyes. This statue is also known as Da Tonte.

Religion

Hinduism in Bali has transformed into what is known as "Indo-Balinese religion," which encompasses the fundamental tenets of classical Hinduism, many concepts from Buddhism, as well as ancient Balinese beliefs.

The lives of Balinese are infused with the service of divine forces, and they associate most aspects of their lives with the influence of these forces.

Ritual Structures

Not only in each village, but essentially in every courtyard, there is a temple where Balinese conduct daily religious ceremonies.

The village center, marked by a crossroads, is considered a sacred place where the intersection of "kaja" directions (toward the mountains, representing benevolent forces) and "kelod" directions (toward the sea, representing malevolent forces) occurs.

In such a location, a sculpture of one of the deities is usually installed, and in close proximity, the mandatory temple structures for each Balinese village are situated, with their placement determined by the sacred "kaja-kelod" coordinate system for the Balinese.

Thus, the main temple – "Pura Puseh," which is believed to be the place of ancestral spirits, is located closest to the mountain direction.

"Pura Bale Agung," or "Pura Desa," serving as a temple for daily worship of the gods, is situated right in the village center.

And finally, "Pura Dalem," associated with the gods of death and the underworld, is built closer in the direction of the sea.

In the central part of Balinese villages, you'll also find the "vantilan" - an arena for cockfighting, as well as an open space near the obligatory village banyan tree, under the immense shady branches of which people can seek refuge from the heat. By the way, the "vantilan" is also considered a sacred place, as the blood spilled during cockfights is viewed as sacrificial.

Banjar or Community

Within the space between the main temples of the village, you'll typically find residential structures, forming the lowest administrative unit in Bali, known as "desa" or village (at the urban level, this is referred to as "kelurahan").

Each "desa" can consist of several compactly organized residential quarters known as "banjars." They can also be called communities.

Frequently, these "banjars" are organized based on professional principles, and due to the high population density in certain areas of Bali, natural boundaries between them are often rivers. Often, rice fields, forests, and other natural features are located at the external boundaries of a "banjar."

In fact, it is the "banjars" that serve as the main social units in Bali, defining the roles of all members of traditional Balinese society. Every married man residing within the territory of a "banjar" is required to be a member.

Essentially, each "banjar" functions as a kind of cooperative, where members, on one hand, have shared ownership of a meeting pavilion called "bale banjar" or a traditional gamelan orchestra, and on the other hand, they assist each other in organizing religious ceremonies, conducting family celebrations and rituals, as well as during crisis situations.

Even while living in cities, Balinese individuals usually participate in various events organized within their native "banjar," and these units play a significant role within urban settlements, not just rural areas.

For Balinese people, a "banjar" essentially serves as a social fortress where they can seek refuge during life's hardships. This is why, for a Balinese individual, the most severe punishment is being excluded from the "banjar," which signifies deprivation of assistance, potential property confiscation, and expulsion from the "banjar" territory. Additionally, after death, such an outcast is likely to be denied a burial place in the village cemetery.

Within the "banjar," a Balinese person doesn't feel alone. They know that if needed, someone will always come to their aid. Even after a person's death, members of their "banjar" pray for the reincarnation of their soul and its rebirth within the same community.

Desa or Village

Several "banjars" form a "desa" or "pavongan," representing a semi-autonomous structure where life is significantly influenced by internal rules and traditions that have developed over several centuries. Because of this, each "desa" elects its leader, responsible for the village's internal affairs and the preservation of its traditions – called "lelian adat" or "bandesa asat." This leader also serves as the head of the village council, composed of all married men from that "desa."

Such a "village elder" can only be elected from among the full-fledged members of this community, known as "krama desa," and their term is unlimited.

Simultaneously, each "desa" is part of the state structure, forming a higher administrative unit called "kecamatan" or district. In this case, the affairs of the "desa" are overseen by an appointed official known as "perbekel" or "bandesa," who is accountable to the regional authority.

The population of a "desa" typically ranges from around 200 to 1,000 or more individuals. If each "desa" consists of several "banjars," these, in turn, are subdivided into several "tempekan" or village clusters. The latter are further divided into ancestral residential complexes called "pekurenan," constructed behind high fences.

In the village, a Balinese person's life is influenced by various connections with their neighbors and relatives. Often, Balinese individuals unite based on their primary occupation, forming groups known as "seka." Interactions within these "seka" are strengthened through joint religious ceremonies. Apart from professional "seka" groups like the "seka gong," which gathers gong producers, there are also youth groups, women's groups, and so on.

Household Organization

In contrast to the open communal and religious life of the Balinese, where they gather for numerous religious ceremonies or discussions under the beringin tree, or to collaboratively build irrigation structures, their family life is private and takes place behind high fences that surround their homes.

An individual residential complex, where members of the same lineage reside, is referred to as "dadia."

In each residential complex, in its eastern part facing the mountains, there is a family temple. Also, closer to the mountains, there is a structure known as "meten bandung," where the owner's family resides, including their parents, and sometimes grandparents.

In the eastern part of the complex, you'll also find a pavilion called "bale dangin" or "bale gede," where family ceremonies such as weddings, tooth filing ceremonies, and others take place. Children may also sleep here, although they usually spend the night in a structure located in the western part of the complex called "bale dauh."

In the part of the complex closer to the sea, buildings with specific functional purposes are situated: a kitchen, a barn, a pigsty, as well as a bathing area.

Worldview

The Balinese worldview entails the constant exaltation of life as a gift from God. It is through the aforementioned units of Balinese society that a continuous expression of gratitude to the divine principle takes place, thereby imbuing all aspects of a Balinese person's life with spirituality: reverence for ancestors occurs within the framework of family units, thanksgiving for material well-being takes place within professional associations, and ultimately, village communities (banjars) offer prayers for the preservation of their territories.

Certain Balinese individuals, engaged, for instance, in 12 different associations, practically participate in various religious ceremonies almost daily throughout the year.

Caste System

An essential aspect of Balinese reality is the division of society into castes, known as "wangsa," with the three highest castes - Brahmins, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas - collectively referred to as "trivangsa," while the lowest caste, Shudras, is called "jabā." The three highest castes make up only about 3% of Bali's total population.

As for the lowest caste, its members mostly seem to be descendants of the Balinese people who inhabited Bali prior to its subjugation by Majapahit in the 14th century.

Naming System

Each caste has its own naming system, which cannot be used by members of other castes.

For aristocratic families of the higher castes, names include titles like "Ida Ayu" for women and "Ida Bagus" for men in the Brahmin caste, "Cokorda," "Anak Agung," and "Dewa" for the Kshatriya caste, and "Gusti" for the Vaishya caste.

Children of the Shudra caste are given names based on their birth order within the family. Thus, the first child is named "Wayan," the second is "Made," the third is "Nyoman," the fourth is "Ketut," and then the fifth child is again "Wayan," and so on.

Therefore, in conversation, it can be quite difficult to determine which "Wayan" or "Made" is being referred to until their family affiliation is clarified.

Often, a Balinese name includes a particle that indicates gender: for example, "I Made" signifies the second or sixth child - a boy, while "Ni Ketut" represents the fourth or eighth child - a girl. However, even in the higher castes, names that denote birth order are present: the eldest child is given names like "Raha," "Putu," or "Kompyang," the second is "Raj," the third is "Aka," and the fourth is "Alit."

Castes in Language

Depending on their caste, one of the variations of the Balinese language is used, which is divided into high style, refined style, ordinary language, and coarse colloquial language. When not knowing the interlocutor's caste, the speaker begins the conversation using the refined variation or the ordinary language, and only during the interaction do the participants adjust their speech according to the caste affiliation of both speakers.

You can add one right now!