For many of those who live in and visit Bali, the problem of the confrontation between local taxi drivers and drivers of online applications, which have gained popularity in the last couple of years, is familiar. In relation to this conflict, there are generally two positions.

Some prefer online taxis and refer to taxi drivers as "taxi mafia." There are those who defend the position of traditional taxi drivers and accept their arguments that they are the owners of their land and can establish their own rules on it.

Business Insider journalist Harrison Jacobs conducted an investigative report by talking to drivers on both sides of the "frontline."

We provide you with Harrison Jacobs' article on businessinsider.com.

"Why should we make foreigners richer?" Taxi drivers measure their strength against Grab in Bali.

In Bali, ride-hailing apps such as Grab and Gojek are the first choice for tourists who want to get around the island.

Taxi drivers have intimidated, attacked, and pursued online taxi drivers numerous times, believing that they violate the unwritten laws of Bali and deprive the local community of income.

It is becoming increasingly clear that the use of taxi-hailing apps is disrupting Balinese traditions and culture in the most unexpected way.

I spoke with over a dozen taxi drivers, online taxi drivers, and ordinary Balinese people who revealed the story of how a centuries-old culture is under attack from new technologies.

Once in Bali, I thought that if I got on the bad side of a gang of taxi drivers, it would be the most foolish trip of my life. I approached a taxi stand on a popular Bali beach with the intention of asking a very sensitive question for Bali.

As I stood under the thatched roof and my translator Ketut introduced me to the drivers, I worried that someone might recognize me because of an incident the previous night that had angered one driver.

The night before, like many tourists in Changgu, I spent time at Old Man's, a popular bar. At 2 a.m., tired and slightly intoxicated, I decided to head home. A taxi driver at the stand quoted me 200,000 rupiahs for a ride home. With the confidence of a tourist who is seen as a money tree, I tried to negotiate. The taxi driver did not yield, angrily pointing to the tariff board on the wall.

As I walked away from the stand, he shouted after me, "You'll walk home!" But I didn't.

I walked out of his sight, called a Grab taxi, and paid a tenth of what the previous driver had demanded.

When visiting developing countries, you constantly try to find the delicate line between supporting the local economy and exploiting it. Sometimes it's easy to draw. Most would agree that it's better to eat grilled fish in a fisherman's shack than an elaborate fish dish in a more expensive restaurant owned by French expats.

But technology has blurred the line.

When I rejected the local taxi and called Grab, a Balinese driver named Kadek picked me up. So what was I doing—pumping tourist dollars or supporting another local resident?

About 5.7 million tourists visited Bali last year. Like everywhere else, ride-hailing apps have become a popular way to get around Bali.

Many of these tourists stay for months, contributing to communities of expats from the US, Europe, Australia who work online or start their own businesses. It is expected that the number of expats in Bali will increase in the coming years.

In Bali, the resistance of taxi drivers to online taxi drivers has sparked an unprecedented and often violent struggle, with clashes with the so-called "taxi mafia." Last year, an Uber driver was brutally beaten by four taxi drivers. Harassment and threats from the "taxi mafia" are common for online taxi drivers and their passengers.

Even before arriving in Bali, I was warned against using online taxi-hailing apps, under the threat of the taxi mafia's anger.

As I traveled to my hotel in Ubud, a city in central Bali known for spiritual healers, yoga retreats, and vegan cafes, I noticed signs with red crosses over the logos of popular online taxi apps and calls to support the local economy.

In the eyes of Balinese taxi drivers, online taxi companies deprive the local community of income and provide nothing in return.

In the taxi stand in Changgu, I met Wayan Tono, a 50-year-old head of the transportation department of Batu Bolong beach, a cooperative consisting of 165 drivers from the local banjar.

Tono, a proud man in a shirt revealing a hairy chest, explained that online taxi apps are destroying a system that has been built on Balinese culture for centuries.

Every village in Bali is divided into several banjars, which typically consist of a maximum of 500 people. Each banjar operates like a cooperative, where its members make decisions on all aspects of banjar life in a general council. This includes matters related to roads in the banjar, land use, punishments for criminals, and the conduct of religious ceremonies. Drivers in Tono's cooperative are all members of the Batu Bolong banjar.

When Tono says they are locals, it doesn't just mean Balinese; it means people from the land on which he stands. Since the launch of ride-hailing apps in 2015, tensions have been escalating. Taxi drivers treat online drivers even worse than the companies themselves because these drivers are aware of the unwritten Balinese laws.

In the months following the app launches, drivers placed signs in banjars indicating areas off-limits to online taxis and began aggressively defending territorial boundaries. Drivers protested multiple times in Denpasar, the capital of Bali. They called on the governor to ban apps that, in their opinion, set unfair fares with which they could not compete.

In Tono's eyes, Grab takes away earnings from his community and provides nothing in return. He mentions that his drivers build roads in their area when the provincial government does not. Many online drivers come from other Indonesian islands, such as Sumatra or Java.

"It's simple. This is my village. I work here. I respect this place," says Tono. "We all work together. And the money we earn, we share and use together."

In Bali, taxi prices are twice as high as Grab or Gojek prices. However, taxi drivers say they cannot lower their prices because 30% goes as a tax to local communities.

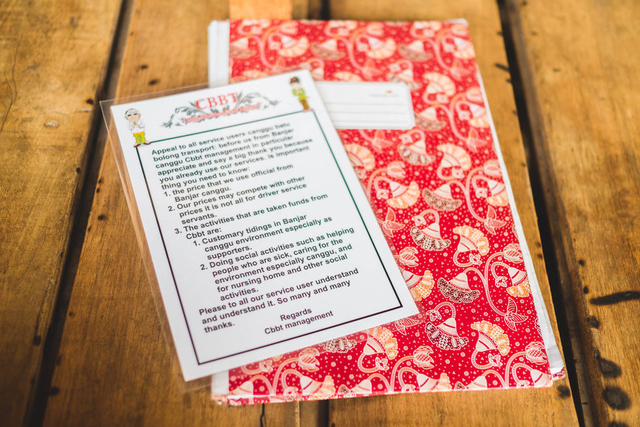

The Batu Bolong cooperative in Changgu keeps a laminated paper explaining to tourists why their prices are higher than those in online taxi apps.

Rules vary from banjar to banjar, but they all adhere to a common principle. Drivers are allowed to pick up passengers only within their banjar. This means that the trip is priced as a round trip to cover the cost of fuel.

In the Batu Bolong banjar, drivers do not receive the full amount from the fare. 10% goes towards road improvement, 10% for religious ceremonies, and 10% for traditional Balinese police, known as pecalang. Pecalangs handle matters that the regular police do not intervene in—essentially everything except serious crimes. Another 10% goes to the taxi cooperative. These funds are used for lawyers, car insurance, and loans for drivers in need of financial assistance. If there is a surplus, it is distributed to the drivers at the end of the year.

It's not surprising that a ride on Grab can cost 10 times less.

The Balinese taxi system is based on a queuing order. Drivers on shift put their names in a queue and wait for their turn. Sometimes, they spend an entire day without earning anything.

Taxi drivers don't want to surrender to the threat of new technology. "Bali is not an app. We have traditions in Bali. Maybe in Java, they don't have traditions. But in Bali, we do. Maybe in some other country, it doesn't matter. But it matters to us," said one driver who refused to give his name.

When I told him I took Grab the previous night, he became furious, asking if I would like it if someone from the internet did my job for a fraction of my price. When I explained that this is precisely what happens in journalism and many other fields, it did not convince him.

After three years of disputes, the issue remains unresolved.

In 2016, violent protests occurred in Jakarta. Taxi drivers clashed with online drivers. In the following years, there were frequent confrontations, pursuits, and threats from taxi drivers.

The Bali Transport Agency imposed a temporary ban on online taxi services, while the Indonesian Ministry of Transportation declared online taxi applications illegal. To continue their operations, Grab and its drivers had to behave like a traditional transportation company – obtain licenses, pass driving tests, and use meters.

Government regulations did little to stop the operation of online taxis or ease tensions. In 2017, a brutal assault occurred on an Uber driver who attempted to pick up a passenger at a hotel in Seminyak. The driver was demanded to pay a fine of 500,000 rupiahs. When he refused, taxi drivers pulled him out of the car, beat him, and vandalized his vehicle with stones and sticks. According to testimonies from taxi drivers and drivers, many such incidents go unreported to the police.

However, the brutality did not dissuade Indonesians from wanting to work with Grab or Gojek. The demand for transportation among European and Indonesian tourists is too high.

There is comfort in being somewhere, opening an app you use at home, and finding that it works just the same.

An Uber driver named Budi told Southeast Asia Globe that in a good month, he could earn $1,800. Taxi drivers I spoke to responded that they earn $212-$354 in the busiest months. The minimum wage is $125 per month.

For a moment, I thought my perception of taxi drivers as members of the taxi mafia was accurate. But Gede Hendra, the head of the driver cooperative, suggested I look at the situation from a different angle: "Why should tourists pay the same price for a taxi as poor locals?"

When I rode a Grab taxi from Old Man's, I was sure I had done the right thing with the taxi driver. I believed everything said about them was true. They were just looking for wealthy tourists. The price my Balinese friend deemed normal for my trip was exceeded by more than twice.

Gede Hendra, vice president of the Changgu Beach Transport Association, suggested I consider everything from his perspective: "Why should locals pay the same prices as tourists from the USA, Europe, Australia, countries where people often earn 10 times more than locals? Isn't it clear that Balinese, who open their communities to tourists and create infrastructure, should get jobs from tourists?"

"We don't want to stand aside from the tourism industry. We want to participate in it and make a living. We care about the development of this area. And online taxi drivers don't care about anything. They just come, pick up passengers, and leave," says Hendra.

"We want to provide services to tourists and protect Bali."

Hendra stated that his drivers want to protect their community from turning into another Kuta, an area where locals receive little profit.

Hendra even emphasized that he doesn't mind if locals use online taxis. However, this position was not supported by drivers from other local taxi stands.

There is no public transportation in Bali. Most locals buy scooters or motorcycles to move around the region. Hendra said that if they need a cheap ride to the hospital, he won't stop them from trying to call Grab.

As tourism in Bali has developed, and savvy tourists sought places to avoid Kuta, Canggu has flourished over the last 5 years. The beaches in Canggu are relatively clean, and the area has gained a civilized street full of French bakeries, brunch spots, tattoo salons, and beach bars. Hendra is happy with the influx of tourists, but he doesn't want Canggu to become another Kuta, where almost all the revenue goes to foreigners.

Hendra is concerned that companies like online taxi apps could drive down prices for other tourist services, from guides to restaurants and hotels.

"How can you provide good service if the price is too low?" he asks.

In the end, it all comes down to money. And this is a standard problem that online taxi companies have faced in any market they entered. Balinese taxi drivers see that their market is saturated with competition, shockingly low prices, and intermediaries they must pay to get work.

"Imagine living here and being out of work for a while. Hunger torments you. And someone comes and takes away your client. Wouldn't that make you angry?" Hendra asks.

Hendra says that the image of the "taxi mafia" is spread by online taxi drivers for their own benefit. He claims that online taxi drivers know where they can work and where they cannot. If a newcomer comes to their banjar, they stop him and explain the situation. In most cases, the driver leaves. Sometimes it escalates into a verbal altercation.

I wanted to believe Hendra, whose post looked one of the most active. But I was skeptical that others were not behaving more aggressively.

However, tourists, bloggers, and online taxi drivers continue to talk about scary adventures with taxi drivers. Many tourists and bloggers write about their conflicts with the so-called "taxi mafia."

Kate Alvarez, a journalist living in the Philippines, described in her blog in February how a group of taxi drivers chased her around Ubud while she was waiting for an Uber driver to pick her up. She hid in a cafe, canceled the trip, and called a private driver, whose number she kept. When this driver showed up, the taxi drivers interrogated him.

Budi, an Uber driver, told Southeast Asia Globe that he was constantly pursued and intimidated by taxi drivers. During one incident, Budi recounted how a taxi driver tried to open the door of his car after he picked up a passenger. When they couldn't, the taxi driver and three friends cut the letter U in the back of the car.

He starts working at 4 am because at that time, you don't often encounter other drivers.

As I was explained, territories are not only limited by banjars. In Bali, local gangs control shopping centers, beaches, tourist attractions.

If a taxi driver wants to work in a certain area, he must pay a tax, which sometimes amounts to several thousand dollars. After that, he is issued a document that allows him to work in a specific area.

Many territories are controlled by the so-called "keluarga besar" ("big family" - keluarga besar) – large gangs that control security in certain villages and oversee many legal and illegal processes. It can be imagined that if online taxi drivers cross these groups, retribution can be cruel.

Some drivers are tired of conflicts with tourists and online taxi drivers. Nyoman Tritata, a 49-year-old Balinese, operates a taxi stand near the Tanah Lot temple. Previously, his stand was inside a hotel, and it brought him a lot of business. But it closed, and he had to move the stand to the road.

Many Tanah Lot visitors come in their own cars or with private drivers. Tritata and his colleagues sometimes spend days without earnings.

"For me, it's better to find work than to go out and protest. The government doesn't care about what we say," says Nyoman.

Tritata lowered prices to compete with Grab. Some of his drivers registered with the app. They don't follow Grab's rates in their bandjar. But if, during a trip, they travel across the island, they take Grab trips on the way back.

The more I talked to taxi drivers and online drivers, the clearer it became to me that the ethical choice is to support local taxi drivers. But it's challenging because they are more expensive and less convenient. It seems like their disappearance is only a matter of time.

In a sense, I felt that taxi drivers were fighting an unstoppable force. On my last day in Bali, I considered taking a taxi to the airport. But the prospect of dragging my suitcase to the nearest taxi stand and paying 2-3 times more didn't appeal to me. I called Grab.

My driver was a 20-year-old hospitality university student named Made.

His father had been a driver in Bali for many years, working in the Jimbaran bandjar system. But he sold the car in 2014, tired of the headaches and payments implied by that system. When Grab appeared in 2015, Made's father bought a new car, registered, and started driving again. In his father's opinion, the apps leveled the playing field.

His father encourages him to earn by driving in his free time to have some money and practice English with tourists.

When Made was old enough, his father showed him the bandjar boundaries, outlining where he can and cannot pick up passengers. He says about half of the drivers switched to online taxis. The age of their cars allowed them to register with apps that limit the vehicle's age to 5 or sometimes 10 years. The remaining drivers were resentful because they didn't fit within those limits.

At that time, Made's explanation eased my guilt about using Grab. But looking back now, I realize that wealthier locals win. Those with enough money for a new car. 35% of Balinese live below the poverty line. And the poorest in the bandjar are the losers.

Given the demands of Europeans for technological convenience, it's unlikely that anything will change in the near future.

You can add one right now!